Principles of Visual Design

An overview of the principles used to guide and inform product design decisions, including proportion, hierarchy, emphasis, contrast, and balance.

Michael Croft

January 19, 2023 · 8 min read

Overview

Underlying the specifics of implementation in design are a set of principles which guide and inform key decisions. You may be familiar with some of these principles as they relate to graphic design — such as balance, contrast, emphasis, hierarchy, movement, pattern, proportion, repetition, rhythm, and unity. Although all are applicable, a subset are of particular importance in the context of product design, and essential to designing effective, visually-appealing products. These include proportion, hierarchy, emphasis, contrast, and balance.

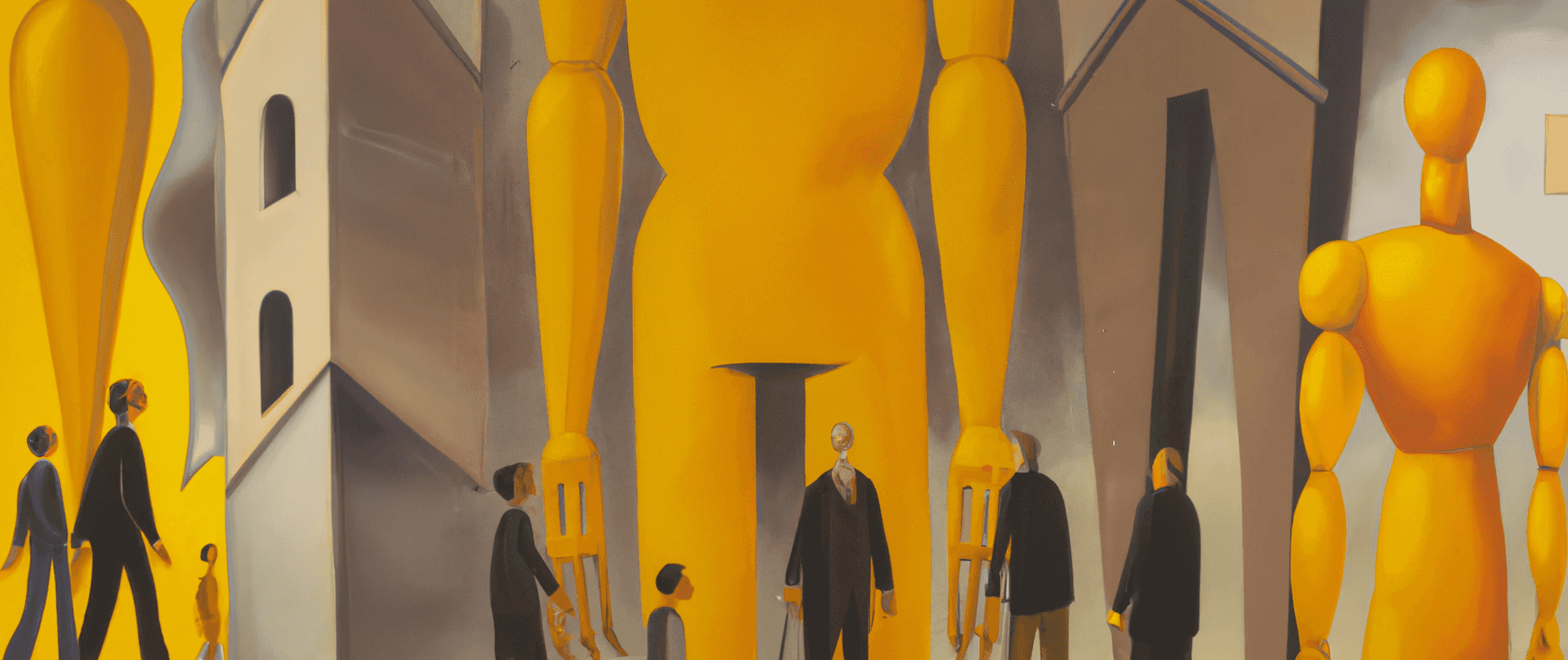

Proportion

Proportion, also known as Scale, refers to the size of two elements or properties of elements in relation to each other. There are no hard quantitative rules about what proportions are considered ‘correct’, and proportion may be varied intentionally to create a different aesthetic. However, extremes at either end of the spectrum — being too large or too small — will look awkward and may affect the speed with which information can be digested. To illustrate how this principle applies to the properties of a single element, consider a button component.

Example

Poor Proportions: Here the space inside the button is too small compared to the text size, resulting in an awkward, crowded look. To improve the proportion, a designer could either increase the space inside the button, or reduce the text size.

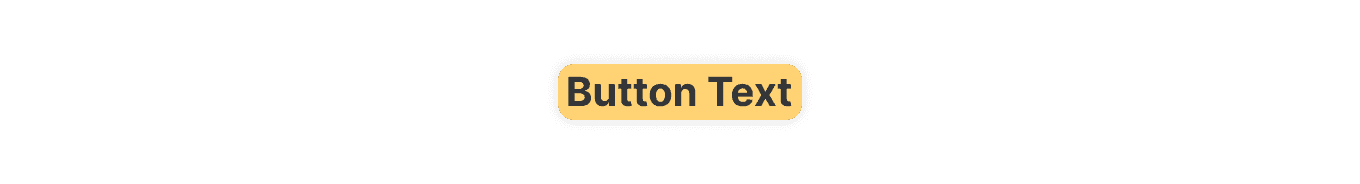

Example

Poor Proportions: Here the space on the left and right is correctly proportioned in relation to the text size. However, the space on the top and bottom is too small, resulting in a vertically-squeezed appearance. To improve the proportion, a designer could increase the space on the top and bottom.

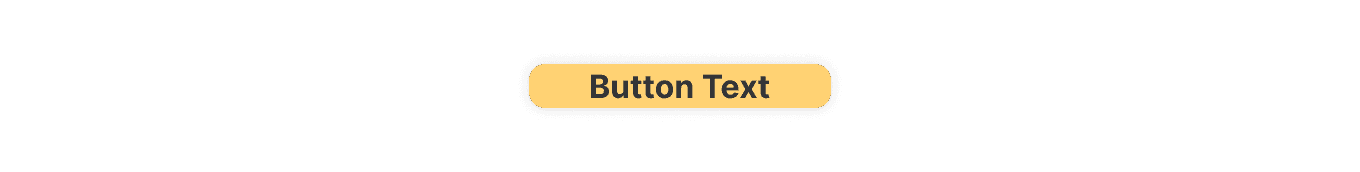

Example

Good Proportions: Here the space and the text size are well proportioned, resulting in a more balanced, visually-appealing design than the previous two examples.

Example

Good Proportions: Here, although the space has been reduced, the button remains well-balanced because the text size has also been reduced to maintain the relative proportions.

This principle is also applicable to the relative proportion between different elements. That is, if a single element has a low density, then other elements should have similar density proportions. To illustrate this, consider a design system with three levels of button sizes:

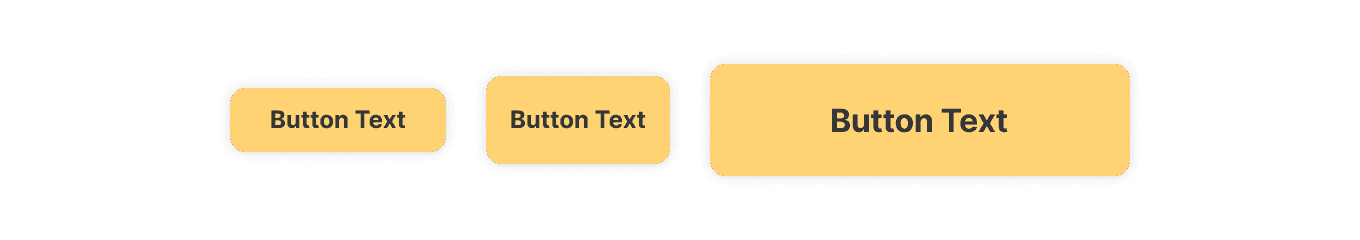

Example

Poor Proportions: Here each button may be considered to have acceptable proportions when considered in isolation. However, when considered as a system, the medium-sized button appears out-of-place, as its proportions are inconsistent with those of the small and large buttons. The spacing above and below the text has scaled up in size compared to the smaller button, yet the text size has remained the same, and the spacing on the left and right has decreased. The result is a button that, although fine in isolation, looks awkward and squeezed when considered in the context of the system of button sizes.

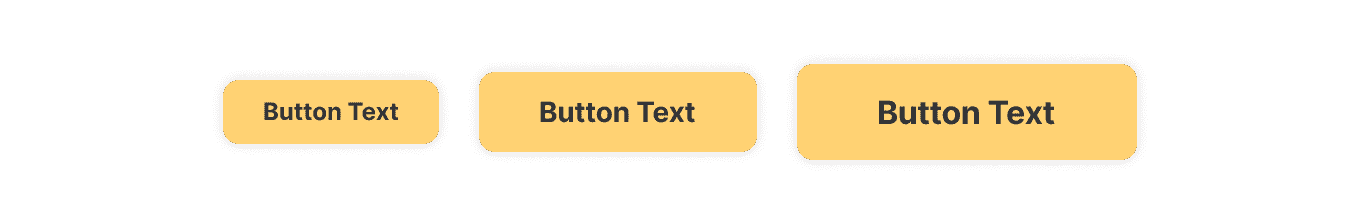

Example

Good Proportions: Here the buttons look well-proportioned in relation to each other — with the text sizes and spacing on all sizes scaling up and down proportionally compared to the other buttons in the system.

Poor use of proportion is one of the most telling indicators of an inexperienced visual designer — and often the underlying issue when a design as a whole appears unpolished. Accordingly, it is essential to spend time developing a sense of proportion to be able to create visually-balanced, harmonious designs.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy, also known as Visual Hierarchy, refers to the use of position, size, and styling to determine the visual order of a page. This involves designing elements to intentionally stand out to varying degrees so as to draw attention to them in the desired order. This may be used to guide users to the most important information or encourage them to take a particular action.

The use of position to influence visual hierarchy is fairly straightforward — the most important elements are placed at the top, and the less important elements are placed below. In more complex layouts, important elements may also be placed further away from larger clusters of elements such that they stand out due to the lesser content density.

Size may similarly be used to increase an element’s visual weight and therefore position in the visual hierarchy. Like position, this is fairly straightforward — more important elements are larger, whereas less important elements are smaller.

However, the use of style to influence visual hierarchy is far more varied. Virtually any attribute of an element may be manipulated to increase or decrease its visual weight. For example, to increase the visual weight of a piece of text, the font weight may be increased, the font color may be made darker or a contrasting color, the text may be italicized or underlined, or it may be placed within a container with a more conspicuous background color.

One caution when applying this principle is to use as few variables as necessary to achieve the desired visual weight. A common mistake made by new designers is to use both a “belt and suspenders” — that is, to elevate visual hierarchy through multiple stylistic attributes in circumstances where only one is necessary. How many attributes are appropriate will be determined by context — namely the relative visual weight of the other elements in the design.

To illustrate the application of visual hierarchy, consider the following examples.

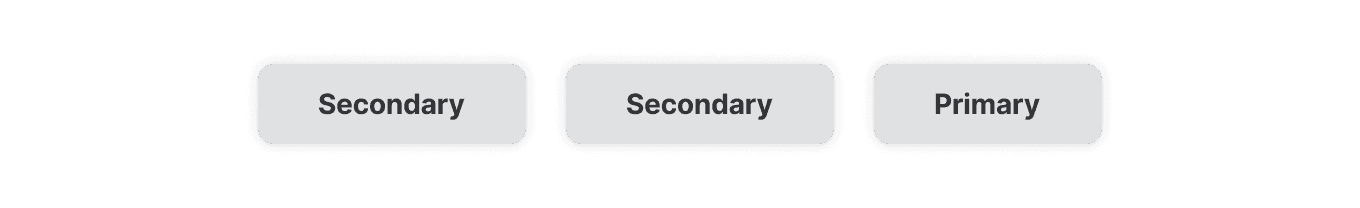

Example

Without Visual Hierarchy: Where all buttons have the same styling, they have equal visual weight, and consequently none is more prominent than the others. If one button is intended to be the primary action, the user must read each label individually to discern that importance.

Example

With Visual Hierarchy: When the primary action is changed to a contrasting color, it has more visual weight and immediately draws the user’s attention.

Example

Without Visual Hierarchy: Where the title and description text are styled the same, it’s difficult to quickly distinguish the two without reading the content.

Example

With Visual Hierarchy: Where the title’s weight is increased, they are considerably easier to skim read without having to read the descriptions.

While there is only a minor benefit in these oversimplified examples, the use of visual hierarchy is essential with more complex layouts with a large number of elements. Failure to define an intentional visual hierarchy may result in designs that are visually confusing or difficult to navigate. This can provide a frustrating user experience and reduce engagement.

Emphasis

Emphasis refers to the use of an element’s attributes to draw attention to it. Naturally this entails significant overlap with the use of Hierarchy — with the narrow distinction that emphasis typically refers to an individual element, whereas hierarchy refers to the visual order of the entire design. However, the purpose remains the same — to draw attention to particular elements over others.

Contrast

Contrast refers to the use of different elements’ attributes to manipulate visual distinction. Like Emphasis, this principle has substantial overlap with the use of Hierarchy, and may be used to draw attention to a particular element over another. However, in product design, it may also be used in the opposite sense to convey additional information. For example, consider how the contrast of form elements may indicate their state.

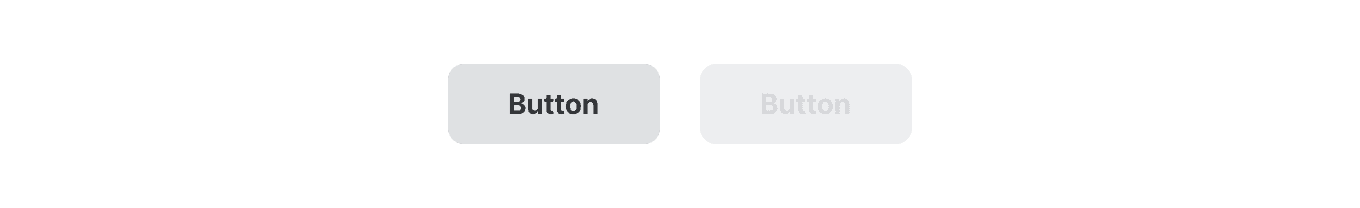

Example

Using Contrast to Indicate State: The button on the left has a standard amount of contrast, and accordingly appears clickable. However, the button on the right has significantly less contrast, indicating that it is disabled and the user cannot interact with it.

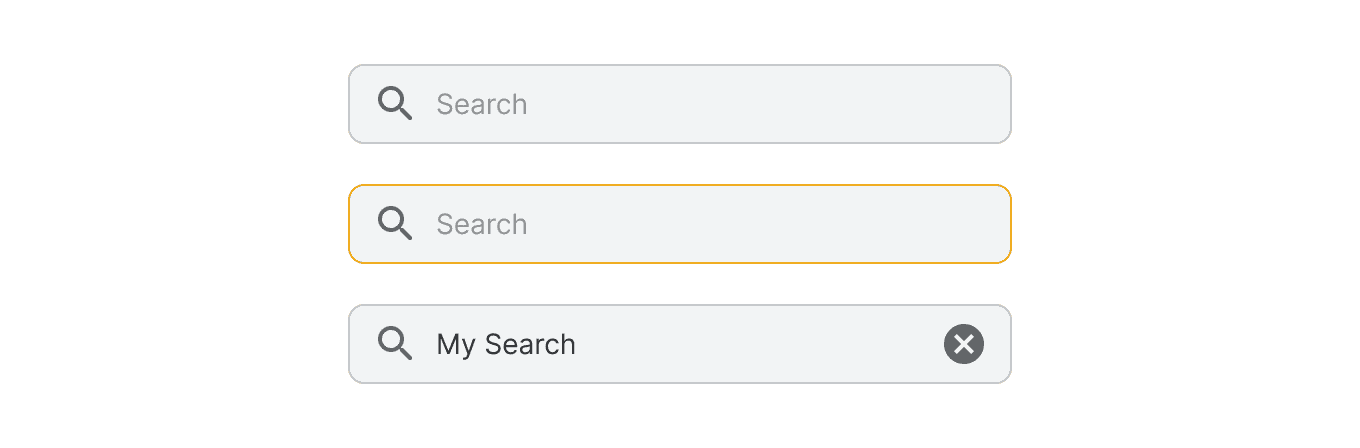

Example

Using Contrast to Indicate State: Here contrast is used to indicate two different types of state for a single input element. The amount of contrast of the text color indicates whether it is a placeholder or a query entered by the user. Similarly, the contrast of the outline indicates whether the input field is inactive or selected by the user.

Balance

Balance refers to the arrangement of elements within a design such as to create a sense of equilibrium. More simply, this means that visual weight should be balanced across a design to avoid areas of a layout feeling empty. An element doesn’t need to mirror the same attribute as the element it’s balancing out — it’s more about the cumulative visual weight of each element. Accordingly, a bright element can balance out a large element, and a colorful element can balance out a larger number of elements. To illustrate this principle. consider a website’s header component.

Example

Unbalanced: A large logo and three navigation links feel unbalanced compared to a sign up link on the right. The result is a design that feels awkward and incomplete — like there’s something missing.

Example

Balanced: With the logo slightly smaller, the navigation elements shifted to the right, and the sign up link converted to a colorful button, the design feels more balanced and harmonious. The result is a more polished, more-complete feeling design.

Another consideration beyond visual weight is how elements’ specific attributes are balanced in relation to each other. For example, leveraging bright colors for two elements may yield equal visual weight, yet still result in an unbalanced design. This may occur where each element contrasts with the rest of the design — but they don’t harmonize with each other. This may be demonstrated by tweaking the colors of the above header component example.

Example

Unbalanced: Both the green logo and orange button have similar visual weight. However, as the two colors clash with each other, the design still feels imbalanced.

Example

Balanced: Reverting the green back to the original blue, the elements still have similar visual weight, but don’t clash, and result in a more balanced design.